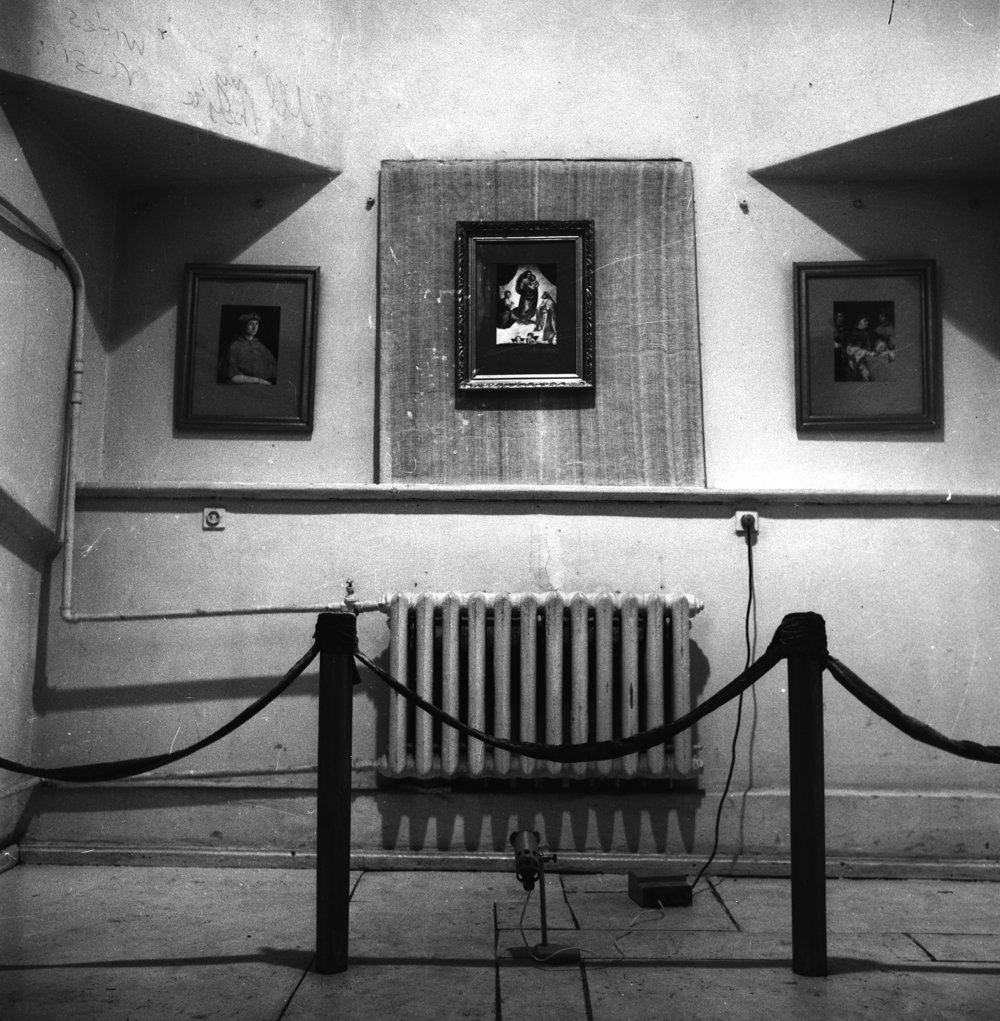

A cross-section of the Zmiievi Valy near the Khlepcha village, 1974. Photo from the Scientific Archive of the IA NAS of Ukraine

In April 2024, ist publishing is presenting the catalogue of Ukrainian Pavilion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale — 'Before the Future'. We are publishing a fragment of one of the research included in the book.

‘Zmiievi Valy Today. History That Protects the Future’

Artem Borysov

At the beginning of March 2022, among the numerous urgent messages about the Ukrainian Defense Forces’ resistance to the rapacious invasion by Russian Federation troops, a message appeared on the official Facebook page of the Ukrainian Ground Forces. A photo of monumental walls near an old farm was accompanied by the caption: "The ancestors have risen. Near Bilohorodka, for the first time, the orcs learned the history of Rus first hand. Orc vehicles could not penetrate the Zmiievi Valy (Eng. The Serpent’s Walls, or Dragon’s Ramparts). Ancient Rus defense systems against the Horde — 2,000 year warranty!" This episode in the defense of the Ukrainian capital became one of the symbols of the heroic struggle for the future of Ukraine.

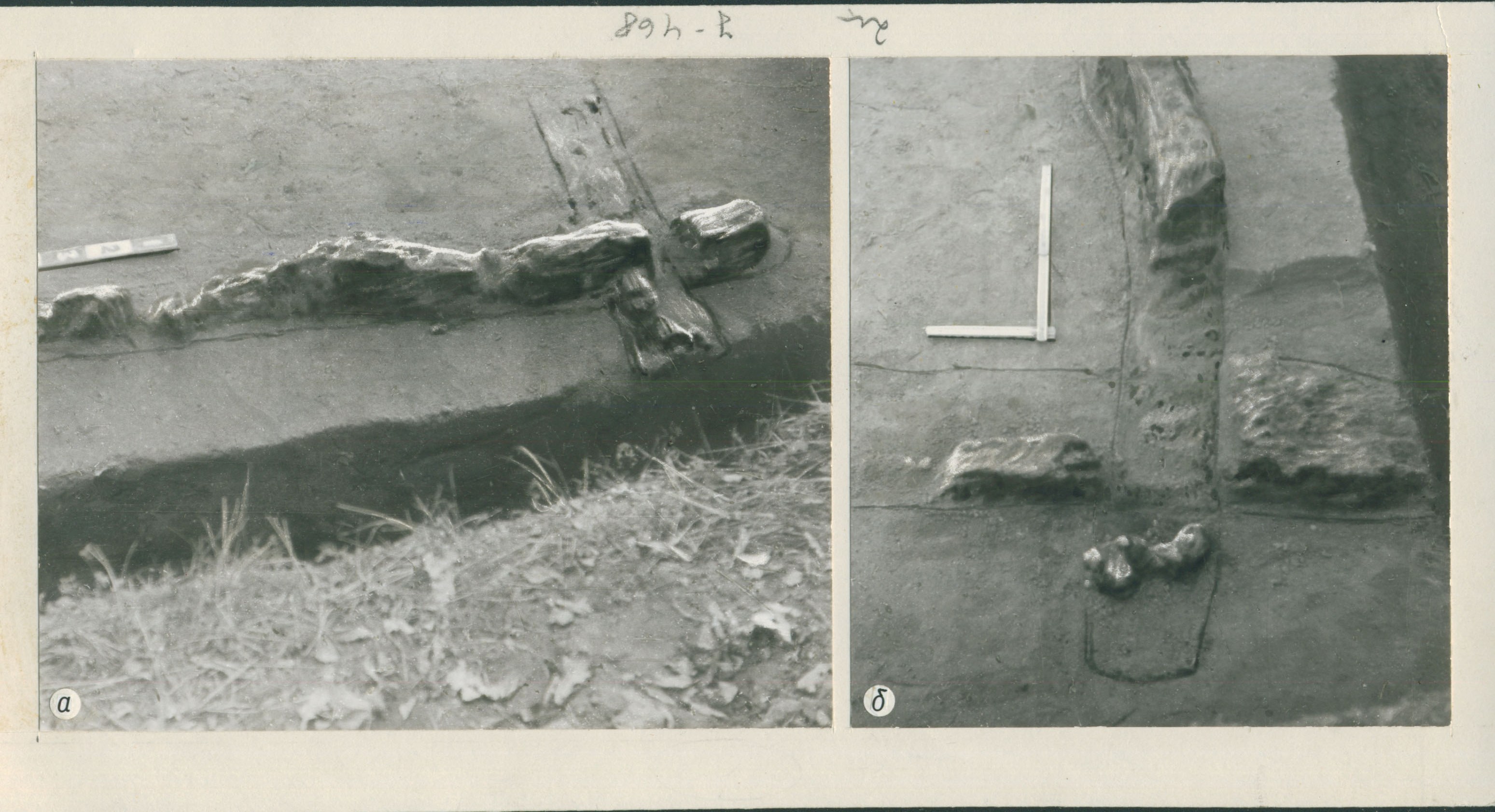

Remnants of wooden structures in the body of the Zmiievi Valy. Photo from the Scientific Archive of the IA NAS of Ukraine

As of March 13, 2022, the post has 20,000 likes, 388 comments, and was shared 3,400 times. Almost all major Ukrainian news agencies rebroadcast this message in one way or another. Some of them even made short videos about it. This episode of the Russian-Ukrainian war, a war for Ukraine’s very existence, emphasized the importance of a reified past for the present and the future.

The territory of Ukraine has been inhabited for about a million years. During this time, human society transformed the surrounding landscape, in particular by changing the natural topography: digging pits and ditches, building mounds and walls. Elongated pits (moats) and earthen embankments (walls) have been known at least since Neolithic times (e.g. the Molyukhiv Buhor settlement or the Mariupol cemetery). Initially, these structures performed economic and ritual functions. Over time, walls and ditches became integral elements of defensive architecture (fortified settlements), and their remains (fortifications, castles, long walls) were incorporated into landscapes formed after militarized periods (belligerent landscapes). Over time, mounds created by the local residents (like various border walls, anti-erosion embankments, and drainage ditches along roads and fields) were added on to these defensive remains from different eras. These elongated structures formed an extremely complex network of elements of different origins, functions, sizes, and structures. In various parts of Ukraine, individual sections of the walls received local names — Turkish Wall, Trojan Wall, Polish Wall, and Zmiiv Wall.

The name Zmiievi Valy was first used for various earthworks on the outskirts of Kyiv. Since the 1970s, the vernacular name has become a scientific term for the remains of a specific type of earthen structure. From the outside, they look like elongated, rather narrow earthen hills. Inside, there are remains of wooden structures — decayed or half-burnt wooden frames. These structures, called horodnias in Ukrainian, acted as internal supports, allowing the height of the walls to be increased. The upper parts of these structures protruded above the surface of the embankment, forming a wooden wall. Because of this construction method, the Zmiievi Valy are also described as wood-earth structures.

In the 10th–13th centuries, Kyiv was the central city of a polity formed on the East European plain, and was ruled by the princes of the Rurik dynasty. This enormous entity, known in medieval sources as Rus, was called Kyivska Rus or Ancient Rus by Russian imperial historians of the 18th–19th century. It was during the development of Rus, under the reign of Volodymyr Svyatoslavovych and his son Yaroslav, that the need arose to create a system to protect the prince’s capital city from the Pechenegs and later from the Polovtsy. The Rurik princes eventually determined that the wooden and earthen fortifications in the immediate vicinity of the city were insufficient for the urban population. A 12th century chronicle recorded an initiative by Prince Volodymyr, expressing the need to build fortifications south of the city along the Stuhna River.

These linear walls stretch for tens of kilometers — sometimes along river floodplains or crossing the space between river valleys. Some segments are combined with hillforts, which are the remains of fortified settlements and fortresses that predated the new linear walls. The combination of these two types of defensive structures — the Zmiievi Valy and hillforts — forms a defense system aimed at protecting against attacks by nomadic peoples from the steppe. Surprise campaigns were the main tactic of nomadic tribes. The Zmiievi Valy prevented the armed cavalry units from approaching. The wall’s position blocked cavalry from moving along the shortest route to Kyiv. Defensive fortresses were located near the largest fords crossing the rivers (Ros, Irpin, Zdvyzh). When the invading army set fire to the wooden parts of the structure to destroy the barrier, they revealed their presence to the defenders. Thus, it was possible to mobilize the necessary forces and means for the defense of Kyiv and the surrounding settlements. This fortification system gradually forced the nomadic formations to bypass the Zmiievi Valy, which increased the distance of their military campaign route, the time required to mount an attack, and the risk of exposure.

The Zmiievi Valy in the village of Plysetske, 2023. Photo: Artem Borysov. From the archive of the monitoring archaeological expedition of the IA NAS of Ukraine. Head of the expedition Vsevolod Ivakin

According to archaeologists and researchers of the Zmiievi Valy, a detailed survey of the territory preceded the actual construction of the fortifications. For instance, Mykhailo Kuchera and Andrii Tomashevskyi indicate the existence of a special "service" for a preliminary survey of the territory for future construction and also an "engineering and fortification service." The use of two types of wooden structures, the successful excavation into the surrounding landscape, and the scale of the construction point to its planned, centralized nature. Given the structure of the walls and the scope of the works (their length is more than 900 km), they could only be constructed under the authority of the Prince of Kyiv and carried out by the combined efforts of Rus. Archeological field research has revealed two phases of construction — under Prince Volodymyr Svyatoslavovych and his son Yaroslav. The calculation of the amount of work performed and the data from the Rus' chronicle about the events from the 10th to the beginning of the 12th centuries indicate that the efforts of 3.5 thousand builders were used in several stages, totaling 19 years. Both excavation teams with wooden shovels and iron sheaths (known at the time as stilts) and highly skilled woodworkers were involved in the walls’ creation. The large-scale construction required the involvement of additional people to provide housing, food, and protection for the builders. The creation of the walls and fortifications around the settlements were managed by the architects, also called horodnyky by ‘Rus’ka Pravda’, a legal document of that time.

Construction of the lines of Zmiievi Valy was not only an act of defense but also a way of developing the territories south of Kyiv for Prince Volodymyr Svyatoslavovych. A particularly vivid example is the land located 200 km south of the princely city. The author of the 11th century chronicle calls this area Porossia, and as we learn from the context, it is located in the basin of the Ros River. In 1032, Yaroslav Volodymyrovych took the first step towards populating Porossia and settled it with captives from the western Russian border (called liakhy in the chronicles). While segments of walls are being built, new fortresses are also constructed in Porossia and inhabited by a population of different ethnicities. The Rurik dynasty used this colonization method throughout the 300-year existence of Rus. Sites like the burial ground for the ethnic Baltic population near the modern village of Ostriv serve as evidence of this.

The construction of the Zmiievi Valy delineated the territories south of Kyiv and encouraged their economic development. At the end of the 11th century, not only the outskirts of Kyiv (between the rivers Irpin, Stuhna, and Dnipro) but also distant Porossia became densely populated. In the 12th century, both Porossia itself and its inhabitants, the Porshany and Black Klobuks, are mentioned in the annals. The latter was a union of several nomadic tribes and clans, who, with the permission of the Kyiv princes, occupied the steppes between the Ros and Stuhna Rivers in exchange for military service. With the strengthening of the union of the Black Klobuks, the defense system of Kyiv began to rely on the mobile units of "its own" nomads, and the importance of the Zmiievi Valy as an integral defensive line started to decline.

Elongated embankments, walls, and lines of fortifications are common ways to fence off one's territory from foreigners. The famous long walls (Ancient Greek Μακρά Τείχη) of the classical era connected Athens with the port of Piraeus. During the Roman Empire, there used to be a defense system similar to the Zmiievi Valy. The Roman Limes was a system of fortifications along the state border of that period, and the remains that exist on the territory of Ukraine are called Trajan's Walls. One can compare the Zmiievi Valy with the famous Great Wall of China. The latter was also large-scale, and incorporated already existing ancient walls. Kyiv's 10th–12th century defense system, including the Zmiievi Valy, was unique because of the longevity of its defensive earthworks, which functioned as belligerent landscapes both before and after the Rus period. These types of landscapes evolved due to military activities, and a large amount existed as separate fortified settlements in the vicinity of Kyiv, long before the city was founded, as far back as the early Iron Age. The remnants of these older fortifications are known as hillforts, which the Rus incorporated into the system of the Zmiievi Valy.

During the rule of the Kyiv princes, a complete defense system evolved. The main sections of this system continued to function even after Kyiv lost its capital status. Thus, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the same landscape areas along the Irpin and Stuhna Rivers became border fortifications and customs points for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Russian Empire. Preparing for the Second World War, the Soviet authorities built the Kyiv Fortified District around the capital. It was a system of concrete firing points and underground command centers. Thus, local belligerent landscapes have at least three periods of active use. During a full-scale Russian invasion in the spring of 2022, these territories became a stage for intense fighting. The positions created by the objects of the military architecture of ancient eras once again became combat positions for the Ukrainian Defense Forces that restrained the onslaught of the occupying troops.

The lengthy periods of formation and effectiveness of these belligerent landscapes and their constituent elements, as structures of defense against the enemy, make clear the need for more detailed study and rigorous protection of the Zmiievi Valy and surrounding territories.

The scale of the Zmiievi Valy impressed people as early as the 19th century. No wonder the first researchers of these structures recorded several legendary versions of their creation. As the legends go, an enormous Snake attacked people and ate them, so, two heroes caught the Snake and, yoking it to a plow, forced it to plow the land. This furrow formed the wall later called Zmiievi Valy. The Snake himself, exhausted, crawled to the river and split open after drinking water.

During the 19th century, researchers gradually collected information about individual sections of the Zmiievi Valy, although they did not visit them in person. Professor Leonid Dobrovolskyi summarized this stage of research. After him, research on the Zmiievi Valy practically stopped. Credit for the exploration revival of these wood-earthen embankments in the Kyiv region must be given to the amateur mathematician Arkadii Buhai. He is an outstanding example of how someone self-taught can contribute profoundly to modern science. Buhai’s activity together with students from Kyiv Pedagogical University (now the Mykhailo Drahomanov Ukrainian State University) exemplifies citizen science also known as crowd science, crowd-sourced science, civic science, networked science. For more than ten years, he researched and popularized the Zmiievi Valy as a topic. This ultimately prompted the authorities to allocate appropriate funds and start exploration of the site within the Institute of Archeology in 1974. History professor Mykhailo Kuchera was assigned to conduct archaeological field research on these cyclopean structures. At the time, Kuchera had already surveyed the hillforts of the former principality of Kyiv and was preparing his doctoral thesis on 10th–13th century hillforts between the Siverskyi Donets and Sian Rivers. His piece on hillforts was published as a separate monograph only after his death in 1990.

In 1974, Kuchera was faced with the task of not only mapping the segments of the Zmiievi Valy in detail but also determining the time and features of their construction and function. Some basic concepts about long walls had already been elaborated in the scholarship, however, no reliable archaeological research had been carried out. Dates obtained from natural, but still imperfect, dating methods (radiocarbon dating) were inconclusive. For ten years (1974–1984), an expedition put together by the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR (now the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine) conducted comprehensive research on the Zmiievi Valy. Professional archaeologists, history and archeology students, and volunteers participated in the expedition. Bohdan Zholdak, a Ukrainian writer, screenwriter, and playwrighter, recalls that Kuchera's archaeological expedition was an opportunity to plunge into a free space, outside of the controlled Soviet reality, which is why he worked as an expedition photographer for several seasons of field work. Archeology students from the Kyiv Pedagogical University, under the leadership of history professor Nadiia Kravchenko (a student of Viktor Petrov-Domontovych), made one of the key discoveries that helped to date the Zmiievi Valy. The group of students (future archaeologists O. Serov, A. Lipkovskyi, and S. Lipnik) were tasked with surveying a line of walls near the town of Vasylkiv, south of Kyiv. Late in the evening, the students appeared on the doorstep of their mentor’s apartment. They showed her a soil-covered iron ax that they had found in the thickets on the Zmiievi Valy. The students had decided to make a stratigraphic multiview orthographic projection of the Zmiievi Valy section as part of their studies. During their investigation of the site, in a section of the carbonaceous layer (the remains of the wooden substructure that had been burnt), they discovered the iron ax, an artifact that would become one of the keys to dating the walls of Kyiv region. The situation was remarkable, as this section had been already examined by Kuchera himself. Only a few centimeters of soil had hidden such a desirable and valuable find from the researcher. This discovery prompted the renewal of the discussion between Buhai, Kuchera, and Kravchenko about the dating of earthen structures.

The archaeological expedition resulted in scientific reports about the field research, articles, and a comprehensive monograph by Mykhailo Kuchera entitled ‘Zmiievi Valy of the Middle Podniprovia’ (1987), which became his doctoral thesis. Over the following decades, isolated papers about the functioning of Kyiv’s defense system in the era of the princes, including specific segments of the Zmiievi Valy, were published. Among these studies, it is worth highlighting Serhii Vovkodav's 2020 monograph ‘Zmiievi Valy of the Pereiaslav Region’, about the defensive structures on the left bank of the Dnipro River, around the historic city of Pereiaslav.

Today, the remains of these walls, originally more than four meters high, rarely exceed two and a half meters. The only exception is one early Iron Age hillfort, the image of which is known locally as the “Zmiievi Valy.”

Segments of the wall are still visible, and appear in satellite images as contrasting stripes next to plowed fields, or as small embankments. A tiny part of the walls remain sodden and overgrown with wild grasses. Separate segments are located in forest areas. In some cases they have been destroyed while clearing the forest and planting new trees.

Pavilion of Ukraine in Giardini at the 18th Venice Biennale of Architecture. Photo: Sasha Kurmaz.