The book of the National Pavilion of Ukraine at the 59th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia relates the history, the different contexts, and the varying interpretations of Makov’s work Fountain of Exhaustion over the years. Here you can read a fragment of the book - in English and Italian.

Pavlo Makov

Fountain of Exhaustion. Acqua Alta

Second curatorial statement

Today, while writing this text, Ukraine is defending itself from military invasion. The army, volunteers, and community services guard the cities and restore the infrastructure with various weapons in separate areas under pressure and shelling. The 32nd day of the full-scale Russian-Ukrainian war is underway. They haven’t managed to take over Kharkiv, a city with one and half million inhabitants; thus, they attempt to erase it with artillery and shelling, seeking to overtire the citizens by depriving them of their homes, water, food, and medicine. They are trying to exhaust Kharkiv.

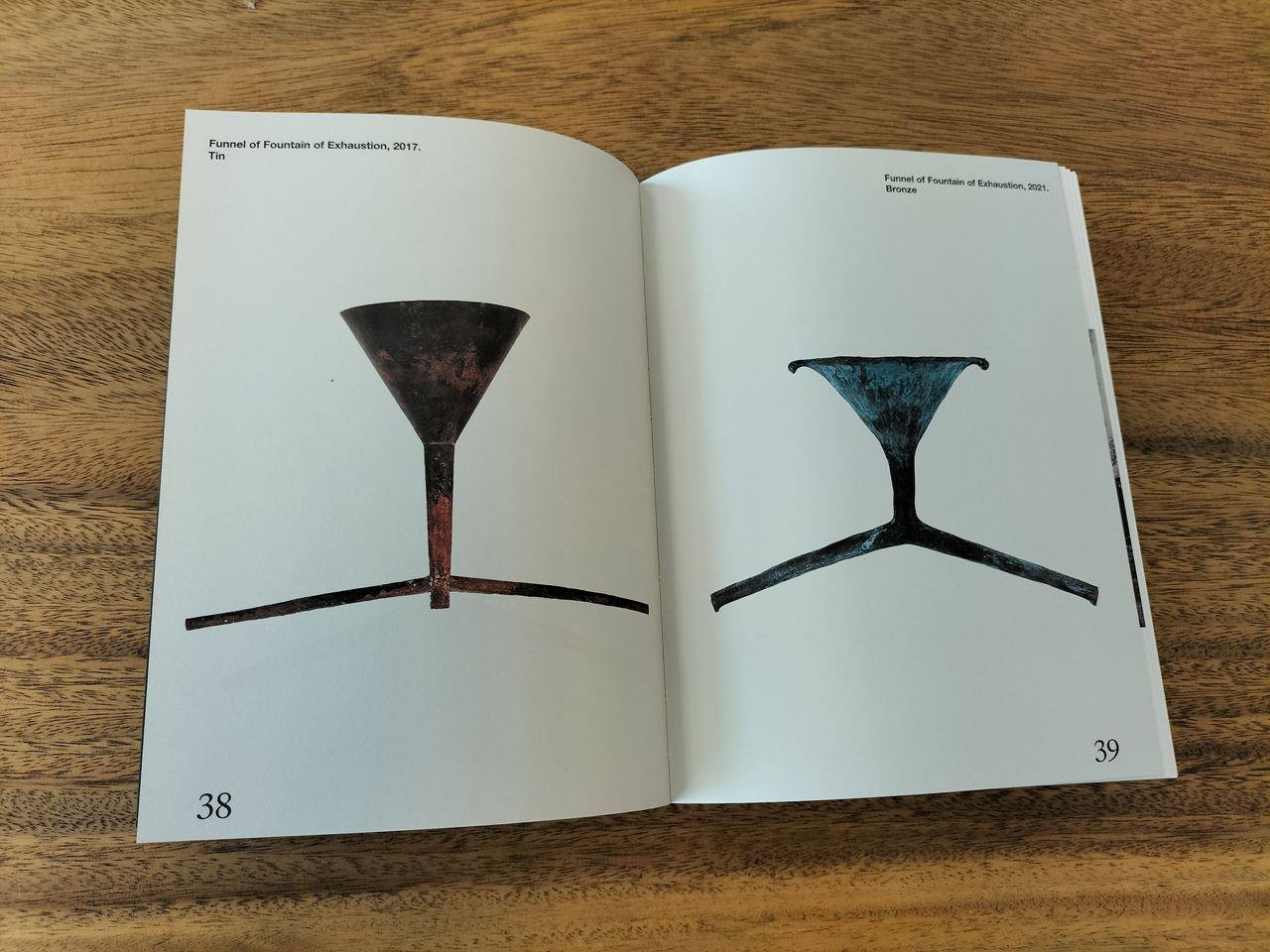

Kharkiv is the city of Pavlo Makov, where, in 1995, he created his Fountain of Exhaustion — a paradoxical symbol of life in a big Eastern European city. At the end of the 1980s, Makov decided to stay here for a longer, within a circle of close and exciting people, in a landscape he wanted to research and talk about in his own works. Makov identified himself as an artist of the place. He documented and revealed local myths and phenomena — the rivers, the fountains, the flat of the outsider-artist Oleh Mitasov, the botanical garden, the targets, the tin soldiers — and engraved them into the chronicles of his artistic practices.

In 1991 in the all-Ukrainian referendum, Makov voted for Ukraine to declare its independence. For the following years, he participated in numerous international exhibitions, where each time, he had to decipher his place of residence. He was asked over and over: “Ukraine? Where is it?” In this way, a particular concept of Utopia appeared in Makov’s artistic practice, a place that is nonexistent to many, yet life there continues on its path. UtopiA — in short, UA, like Ukraine.

In 2014 the Russian army first invaded Ukraine. After the events of Euromaidan, abusing the state of transition, the Russian Federation annexed Crimea and attacked the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. The war postponed the exhibitions, and selling artworks with proceeds donated to the army, military doctors, and internally displaced people became a standard form of artistic action. Concrete blocks, a modular wartime material used for building defensive structures and road block-posts, appeared in Makov’s works. In the gallery spaces, Makov used downscaled models of concrete blocks to make a city plan and a significant foundation for the new reality. In his drawings, a block appeared as a paradoxical part of a garden: it filled private places and divided different worlds. As if in Calvino’s Invisible Cities: on one side — hell, on the other — something that is not; something that needs life support, attention, and care.

The first works by Makov were related to the Kharkiv landscape and combined urban relief with the anatomy of the human body. The first autopsies in Europe and the further appearance of anatomical theatres took place during the Age of Discovery. One could assume that similarly, today, the full-scale invasion of the Russian forces in Ukraine coincides with an age of discoveries of Ukrainian culture.

Since 2014 Makov has been reiterating a thesis on the fundamental role of culture in wartime: “Without an understanding of what Ukrainian culture is, both Europe and the whole world cease to grasp what is being lost in this war”. For the European gaze, the fires, terrorist attacks, and catastrophes are as painful, as the massive losses, devastating shootings, and mass murders committed in the extermination of Ukraine are unnoticeable.

Let’s walk alongside these ruins. Clearly, we are very much secured: there is no broken glass under our feet, no burned wood and crushed stone, no feeling of an explosive wave going through the ground and air, no rattling sound of cruise missiles over our head. No effects of this presence, so well-known to the artist Pavlo Makov. Today, on the 32nd day of the war, more than a thousand residential houses, schools and hospitals, an art museum, and an opera house have been destroyed. Shells have fallen on Independence Square, where the constructivist Derzhprom building — where Vasyl Yermilov showed his works - is standing; on Karazin University, where three Nobel laureates worked at different times; on the place where Walter Gropius planned to build a theatre; on the Slovo house, which was built and inhabited by a generation of poets and artists known as the Executed Renaissance. We could walk along the itinerary of Makov’s places, close to where the rockets fell. The optics of war, as optics tuned to the detailed history of the Fountain of Exhaustion, allow us to follow thirty years of the artist’s practice to be connected to the flowing states of the Kharkiv landscape.

In the etchings, photographs, objects, and artbooks from the 1990s to the 2000s, two long-term motifs are evident: targets and tin soldiers. In 1996 Makov made a photographic archive of male and female targets found in the Kharkiv schoolyards — the unsettling remnants of the Soviet system of education with military training at its core. An image of the target was one of the metamorphoses of the human body in Ukraine-Utopia: bodies with a permanent existential threat of being under the sight of a gun. Another image — a tin soldier and a conscripted toy army followed the Utopia citizen from their childhood. Since 2001, Makov has kept personifying his tin veterans: he photographed them separately and printed their portraits on a full-size human scale. He mystified their diaries in the made-up tin language. In 2003, thirty metres from the place of an unrealised Fountain of Exhaustion installation, Makov sent a paper flotilla down the Kharkiv river to a toy war — to the siege of the Pentagon. In 2010, a central theme for Makov became latency, a feeling of an uncovered threat originating from grey stability and wrong happiness. Since 2014, it has been transforming into personal responsibility, and the etchings started depicting concrete blocks. In 2014 he created the work Kharkiv siege; in 2017 — Shelter. Simultaneously, Makov’s themes have become more global, including the cities’ future and the future after humanity. The COVID-19 pandemic made the work Mappa Mundi possible: a giant flat map with room-countries — the biggest ‘zoom-out’ of the place in the artist’s oeuvre.

The war has changed the Fountain of Exhaustion. In response to numerous journalists’ questions, Makov outlines the nature of these changes: “An exhaustion remains exhaustion. Only in time does the work remain in the past. Before the phase of the war that is now, the work could warn about the hazard of our old-world exhaustion and what will follow, but now, this warning is no longer relevant. This work does not warn anymore, rather, it declares”.

In the first statement of the pavilion’s catalogue, we said that over the 27 years of its history, the Fountain of Exhaustion has ceased to symbolise only mid-90s Kharkiv. Its exhibition history brought a broader meaning — a symbol of contemporary world politics, culture, economics, and ecological exhaustion. The war returns it to its local context: Kharkiv, under shelling, at the peak of exhaustion, becomes a local and global challenge, the place — actually, one of the numerous places in Ukraine — in which destiny is inseparably connected with the world’s future. From the very beginning, the point of view of Giorgio Morandi, who could speak about the whole world by looking at it through the window of his studio, was essential for Makov’s practice. A question for today: can the world prevent the complete exhaustion of humanity? It is possible to answer this while looking through the windows of Ukrainian cities.

Borys Filonenko

Lizaveta German

Maria Lanko

Pavlo Makov

Fontana dell'esaurimento. Acqua alta

Seconda dichiarazione curatoriale

Oggi, mentre scriviamo questo testo, l'Ucraina si sta difendendo dall'invasione militare. L'esercito, i volontari e i servizi pubblici stanno difendendo le città e ricostruendo le infrastrutture in alcune aree, essendo sotto pressione e bombardamenti dai diversi tipi di armi. Oggi è il 32° giorno della vera e propria guerra russo-ucraina su larga scala. Non possono prendere la città di Kharkiv con una popolazione di 1,5 milioni di abitanti, quindi stanno cercando di distruggerla con artiglieria e bombardamenti, stanno cercando di torturare i cittadini, privarli di alloggi, acqua, cibo e medicine. Stanno cercando di esaurire Kharkiv.

Kharkiv è la città dell'artista Pavlo Makov, dove nel 1995 ha creato la sua «Fontana dell'esaurimento», un simbolo paradossale della vita nella grande città dell'Europa orientale. Alla fine degli anni 1980, Makov decise che sarebbe rimasto qui a lungo: tra le persone vicine e interessanti a lui, tra i paesaggi che cercava di esplorare e raccontare nelle sue opere. Makov si è definito un artista del Luogo. Ha documentato e manifestato miti e fenomeni locali: fiumi, fontane, l'appartamento dell'artista-outsider Oleg Mitasov, un giardino botanico, bersagli, soldatini di latta, scrivendone a lungo nella cronaca del proprio lavoro.

Nel 1991, in un referendum ucraino, Makov ha votato per l'indipendenza dell'Ucraina. Per i successivi trent'anni ha partecipato a numerose mostre internazionali, dove ha dovuto decifrare ogni volta la sua residenza permanente. Gli veniva chiesto: «Ucraina? Dov'è?». Così, nelle pratiche artistiche di Makov, è apparso un concetto specifico di Utopia: un luogo che non esiste per molti, ma la vita lì fa il suo corso. UtopiA è una abbreviazione di UA, come Ucraina.

Nel 2014, l'esercito russo ha attaccato l'Ucraina per la prima volta. Dopo gli eventi di Euromaidan, approfittando dello stato di transizione del governo, la Federazione Russa ha annesso la Crimea e ha attaccato le regioni di Donetsk e Luhansk. Le mostre furono posticipate a causa della guerra e la forma regolare di attività artistica era la vendita di opere a sostegno dell'esercito, dei medici militari e delle persone costrette ad abbandonare le proprie case. Nel lavoro di Makov sono apparsi blocchi di cemento: un materiale modulare del tempo di guerra, dal quale sono state costruite strutture protettive negli insediamenti e nei posti di blocco stradali. Negli spazi delle gallerie, Makov ha utilizzato modelli in scala ridotta di blocchi di cemento per creare una pianta della città e grandi fondamenta: le basi di una nuova realtà. Nelle opere grafiche, il blocco sembrava essere una parte paradossale del giardino, riempiendo spazi privati, delimitando mondi diversi. È come nelle «Città invisibili» di Calvino: da una parte c'è l'inferno, e dall'altra c’è quello che non è inferno, che ha bisogno di sostegno vitale, di cura e attenzione.

I primi lavori di Makov riguardavano il paesaggio di Kharkiv e combinavano il rilievo urbano con l'anatomia del corpo umano. Le prime autopsie di corpi in Europa e la successiva nascita di teatri anatomici giunsero in un momento di grandi scoperte geografiche. Si può assumere che oggi l'invasione su vasta scala delle truppe russe in Ucraina coincida con il tempo delle grandi scoperte della cultura ucraina.

Dal 2014 Makov ripete la tesi sul ruolo fondamentale della cultura nella guerra: «Senza capire cosa sia la cultura ucraina, né nel mondo né in Europa, non si può capire che cosa si perde in questa guerra». Per quanto dolorosi siano gli incendi, gli attacchi terroristici e le catastrofi nell'UE, così non sono visibili dal punto di vista europeo le perdite su larga scala dovute all'occupazione, ai bombardamenti devastanti e agli omicidi di massa inflitti per distruggere l'Ucraina moderna.

Camminiamo attraverso queste rovine. Naturalmente, sono in gran parte sicure: nessun vetro rotto sotto i piedi, nessun pezzo di legno bruciato e pietra in frantumi, nessuna risonanza di esplosione in terra e aria, nessun rumore di missili da crociera sopra la testa. Camminiamo senza tutti questi effetti di presenza, ben noti all'artista Pavlo Makov. Oggi, nel 32° giorno di guerra, a Kharkiv sono stati distrutti più di mille condomini, scuole e ospedali, un museo d'arte e un teatro dell'opera. Diversi missili sono caduti su Piazza della Libertà, dove si trova l’edificio costruttivista Derzhprom e dove Vasyl Yermilov ha esposto le sue opere, sul luogo in cui Walter Gropius progettava di costruire un teatro, sull'Università di Karazin, dove tre vincitori del Premio Nobel hanno lavorato in tempi diversi, sull'edificio «Slovo», che è stato costruito e abitato da generazioni di poeti, scrittori e artisti, chiamati il "Rinascimento Fucilato", ecc. Si può anche camminare lungo i percorsi dei luoghi di Makov, vicino ai quali sono caduti i missili. L'ottica della guerra, così come l'ottica, è progettata sulla storia dettagliata della «Fontana dell'esaurimento», e permette di tracciare trent'anni di pratica dell'artista, legati agli stati fluidi del paesaggio di Kharkiv.

In acqueforti, fotografie, oggetti e libri d'arte degli anni 1990 e 2000, ci sono due temi di lunga durata: bersagli e soldatini di latta. Nel 1996, Makov ha fotografato un archivio fotografico di bersagli maschili e femminili che ha trovato nel cortile della scuola a Kharkiv, come un’inquietante rimanenza del sistema educativo sovietico con lezioni di addestramento militare. L'immagine del bersaglio era una delle metamorfosi del corpo umano in Ucraina-Utopia. C’erano corpi con un permanente senso esistenziale di essere nel mirino. Un'altra immagine è un soldatino di latta e un esercito giocattolo con equipaggio che ha accompagnato un cittadino dell’Utopia sin dall’infanzia. Dal 2001 Makov ha conferito tratti personali ai suoi veterani di peltro: ha fotografato ogni figura individualmente e stampato ritratti a grandezza naturale. Mistificava i loro diari con un linguaggio inventato di latta.

Nel 2003, a tre dozzine di metri dal luogo della non realizzata «Fontana dell'esaurimento», ha inviato una flottiglia di carta lungo il fiume Kharkiv per una guerra giocattolo, per un assedio del Pentagono. Nel 2010, il tema centrale di Makov era la latenza, un senso di minaccia non manifestata, che derivava dalla grigia stabilità e dalla falsa felicità. Dal 2014 si trasforma in una riflessione sulla responsabilità personale, mentre sulle acqueforti appaiono blocchi di cemento. Nel 2014 si presenta il lavoro «Assedio di Kharkiv»; nel 2017, «Riparo». Allo stesso tempo, i temi di Makov diventano più globali, coprono il futuro delle città e il futuro dopo l'uomo. La pandemia di COVID-19 rende possibile il lavoro di «Mappa Mundi», un enorme appartamento-mappa con stanze-paese, che è il più grande zoom-out di un Luogo nel lavoro dell'artista.

La guerra ha cambiato la «Fontana dell'esaurimento». In risposta alle numerose domande dei giornalisti, Makov ha delineato il carattere di questi cambiamenti: «L'esaurimento rimane l'esaurimento. Solo riguardo al tempo il lavoro è stato lasciato alle spalle. Se prima dell'attuale fase della guerra, il lavoro avrebbe potuto avvertire del pericolo dell'esaurimento del nostro vecchio mondo e di ciò che sarebbe seguito, questo avvertimento non è più rilevante. Ora questo lavoro non avverte, ma afferma».

Nella prima dichiarazione e nel catalogo del padiglione abbiamo detto che, durante i 27 anni della sua storia, la «Fontana dell'esaurimento» ha cessato di essere un simbolo di Kharkiv a metà degli anni 1990 e, in particolare grazie al suo percorso espositivo, ha acquisito un significato più ampio come immagine dell’esaurimento di politica, cultura, economia, ecologia nel mondo moderno. La guerra ci riporta al contesto locale. Kharkiv sotto le bombe, al culmine del suo esaurimento, diventa una sfida sia locale che globale, un luogo – anzi, uno dei tanti posti in Ucraina – il cui destino è legato in modo inscindibile al futuro del mondo. Fin dall'inizio, per le pratiche di Makov, era importante la visione di Giorgio Morandi, che poteva parlare del mondo intero guardandolo dalla finestra del suo studio. La domanda di oggi è questa: il mondo è in grado di prevenire l'esaurimento definitivo dell'umanità? Ora si può rispondere guardando attraverso le finestre delle città ucraine.

Borys Filonenko

Lizaveta German

Maria Lanko